Post by Maira Asif. M.A., Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies, 2024.

The Center for Women’s Global Leadership (CWGL) stood as a beacon of transnational feminist advocacy, leaving indelible marks on the world through its tireless efforts in promoting women’s rights internationally. CWGL was founded in 1989 by feminist activist Charlotte Bunch as a project of Douglass College and was instrumental in the ‘Women Rights are Human Rights’ Global campaign in the 1990s. As I reflect on my experience curating the CWGL exhibition and analysing its extensive resource collection, I am reminded of the profound impact of feminist activism and scholarship, as well as the challenges inherent in bridging the gap between academia and grassroots movements.

There are moments when your faith in the kind of work you want to do is affirmed. The inauguration of “The Transnational Feminist Advocacy of The Center for Women’s Global Leadership Exhibition” was a moment of profound affirmation for me, as I had the honor of moderating a panel featuring esteemed scholar-activists Charlotte Bunch and Radhika Balakrishnan. Their four decades of work at CWGL have shaped feminist discourse and activism worldwide, evidenced by the over 100 countries represented in the organization’s resource center publications. Collaborating with such inspiring individuals and witnessing firsthand the tangible outcomes of feminist social change reaffirmed my commitment to this transformative work. They humored my jokes, gave us feminist gossip and left us with hope that feminist communities are possible.

My delight and enjoyment is evidenced by the pictures from the event. The joy of working with inspiring people, of seeing evidence of feminist social change through archival curation and of finally sitting next to such role models was palpable. My co-curators and the amazing team of Kayo Denda, Ezra Downs and Nicole Blemur have taught me feminist joy of collective work. Joining this project was a serendipitous shoulder tap by Dr. Rebecca Mark at a party when Kayo was seeking assistance for its completion. It felt intimate, personal and powerful to be surrounded by archives, both written and living, of feminist activism. I know this is the kind of work I was to do for the rest of my life. One which makes a mark, one rooted in feminist ideals, one where I can make silly jokes and get compliments on my necklaces.

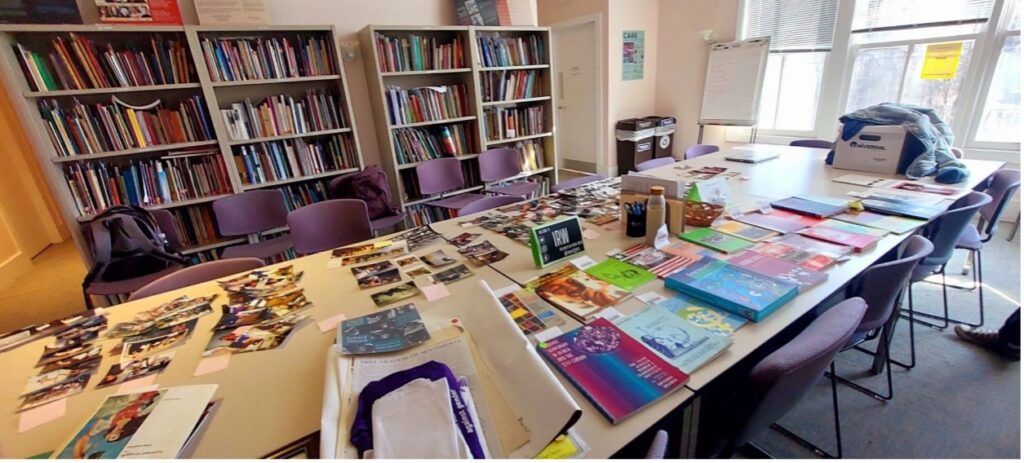

Curating the exhibition and analyzing CWGL’s resource collection provided me with invaluable insights into the intersection of academia and activism. As I delved into the diverse array of publications, from handbooks to conference proceedings to magazines, I was struck by the disconnect between academic scholarship and on-the-ground activism. While academic journals often dominate library databases and pedagogical training, the resources produced by grassroots organizations remain marginalized and inaccessible. The more I went through these publications, one comment from a paper I read stuck to mind about academia’s disconnect with on-the-ground work, “as if nothing has changed on the ground.” None of these books or articles in these handbooks, conference proceedings, radical aesthetic magazines, etc., would pull up in a search engine when we do our research. Only academic journals or likewise academically legible resources get the legitimacy to be part of library databases and, in turn, part of our pedagogical training and research.

So if you want to know what’s being done by organizations on the ground, you have to know the organization, check its website and work. In contrast, you can use keywords to pull up articles on academic research without knowing the researcher or journal name in advance. We assume we have found the divine literature gap when nothing comes up on these search engine results on our question. And why won’t we since the on-the-ground produced resources aren’t similarly centralized and accessible to us? Time is limited in our capitalist hustle culture. We have to churn out more work for work’s sake.

It raises questions for me on: How do we inform our research with praxis, how do we reduce the academia-activist gap, how do we legitimize work of activists and organizations as theory, when our academic institutions structurally limit such intellectual engagement? And likewise when activists and organizations consider theory arm-chair rambling? The disconnect is jarring. This disparity raises critical questions about how we inform research with praxis, reduce the academia-activist gap, and legitimize the work of activists and organizations as theoretical contributions.

As I am wrapping up my last semester of MA program in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and starting to look for work and imagining what kind of work I want to do, the desire to keep this particular dilemma in mind of bridging the activist-academia divide remains an ever-present thought. Do I want to be a scholar-activist or an activist-scholar or neither or both? Let’s see what feminist futures await.

Analyzing CWGL’s resource center material also brought to light the pervasive exclusions present within academic discourse. As a Pakistani graduate student in an American classroom, I have experienced firsthand the challenge of advocating for the inclusion of non-Anglo American perspectives. The labor often falls on us, the outsiders, to educate the white classrooms. If your people don’t have epistemic or geopolitical power, your thought is probably not taught here, and without your physical presence actively championing its inclusion, it probably won’t be anytime soon. Chandra Mohanty, Gayatri Spivak have somewhat broken the barriers into conversations on South Asian thought. Gloria Anzaldua and Cherri Moranga have done the same for Latin America. But heterogeneity as peoples is largely absent in most discussions which centre the North American-European experience as the default human condition. In CWGL’s collection, I found books and reports from organizations working in and with many of these excluded people. We assume people aren’t producing theory and literature to discuss and debate in classrooms. But these thousands of titles said differently. Despite having these precious perspectives in our physical proximity at Rutgers, the challenge to make space for them in our classrooms is foreshadowed by poor funding to social sciences, shadow banning gender and sexuality rights research, teaching and work, and a neo-liberal university who structurally couldn’t care less. Inclusion is for college brochures.

However, CWGL’s collection serves as a testament to the wealth of knowledge produced by marginalized communities around the world. From organizations working tirelessly to amplify these voices, I discovered a treasure trove of literature challenging dominant paradigms and enriching feminist discourse. Yet, the challenge lies in translating this wealth of knowledge into institutional change within academia, where funding constraints and neoliberal structures perpetuate exclusionary practices.

In light of CWGL’s recent closure by Rutgers University, the importance of preserving its legacy and advocating for its invaluable contributions to feminist activism cannot be overstated. I was deeply honored to play a small part in safeguarding CWGL’s resources for future generations. By analyzing decades of advocacy work, I hoped to ensure that the spirit of transnational feminist solidarity continues to inspire and empower activists around the world.

In conclusion, my experience curating the CWGL exhibition and analyzing its resource collection has been a journey of discovery, reflection, and reaffirmation. However, this reaffirmation of feminist values is not just owed to the archives, but the active, warm, kindness of Kayo Denda, Ezra Downs and Nicole Blemur. It was only in the continuous presence of beautiful feminist community that I was able to explore the archives and the exhibition with the joyful gusto that I did. I am truly grateful to have been able to work alongside them all, and I owe the beauty of these few months to them first and foremost.

From L-R: Nicole Blemur, Maira Asif, Ezra Downs, Kayo Denda & Radhika Balakrishnan.

From L-R: Nicole Blemur, Maira Asif, Ezra Downs, Kayo Denda & Radhika Balakrishnan.

Kayo Denda, Radhika Balakrishnan & Charlotte Bunch.

Kayo Denda, Radhika Balakrishnan & Charlotte Bunch.